We’re mixing up this week’s issue with our first deep dive. We’ve talked about the problems of drug costs and drug plan design in nearly every issue, so it’s about time we expound on the problem and provide a few potential solutions.

Complaints about America’s prescription drug prices are durable and pervasive. They are a routine talking point in political campaigns on both sides of the isle. Local news stories cover the challenges some people face in affording their medication. Pharma companies are criticized as ruthless machines prioritizing profits over all else. And there is a lot of truth to the criticisms of biopharma’s drug pricing strategies and the resulting burden placed on patients. But, in our opinion, the issue is more complicated and we should also focus on drug plan design. Most drug plans today function more as reverse insurance schemes, where the sick subsidize the healthy.

Below, we aim to provide a brief overview of the prescription drug space, dive into the plan design problem, and discuss potential solutions. Please keep in mind that this is a very detailed topic with far more nuance than we will get into here. Also, remember that this is our opinion. With that out of the way, let’s dive in!

How Drugs are Distributed and Reimbursed

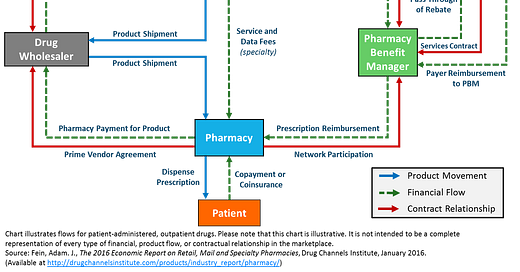

This graphic from the Drug Channels blog lays out the complicated structure of the outpatient prescription drug space. The most important piece to note for our purposes is that the third party payer, i.e. a health plan, outsources prescription drug benefits to pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs). The PBMs process drug benefit claims, manage the pharmacy networks, establish the formularies (what drugs are covered and at what tier), and handle drug prior authorizations (special review and approval process for expensive therapies) on behalf of the health plans.

Importantly, patients typically don’t know who their PBM is. To them, everything looks like it’s coming from the health plan. That means that PBMs are incentivized to prioritize the health plan’s satisfaction over patients’. As long as they keep the plan happy, they make money.

One final wrinkle to touch on in this complicated web is that the major PBMs are now owned by health insurance companies. UnitedHealthcare/Optum acquired Catamaran in 2015 (now OptumRx), CVS acquired Caremark in 2006, Cigna acquired Express Scripts in 2018, and Centene has acquired a number of PBMs since 2006. The Blue Cross Blue Shield plans own the PBM Prime Therapeutics, and most recently Anthem launched its own PBM, IngenioRx, powered in part by CVS Caremark.

How Prescription Drug Plans Work

So what does a prescription drug plan look like? The most important aspect of plan design for this post is the formulary tiering. For reference, a formulary is a list of generic and brand name prescription drugs covered by a plan. Formularies are typically separated into four tiers. Tier 1 usually includes generic drugs and has the lowest copays. Tier 2 usually includes non-preferred generics and brand name drugs and has a higher cost to the member. Tier 3 includes non preferred brands, and Tier 4 covers specialty drugs, which has the highest cost sharing for patients. Below is an example of an actual formulary design from an Aetna health plan. Tier 1 generics can be as cheap as $3 for the member, while non-preferred drugs have $70 copays and specialty drugs require 25% coinsurance payments.

To make matters even more complicated, coinsurance payments are based on a drug’s list price over 50% of the time, not the net price that a PBM or health plan has negotiated. The difference can be enormous. Take Humira, a therapy for various autoimmune conditions and the most commercially successful drug in human history. Humira’s list price, the price that the coinsurance amount is based on, is over $78,000 per year. PBMs and health plans, though, pay an average negotiated rate of only $35,000 per year.

Medicare Part D plans add yet another nuance to plan design, the Medicare Donut Hole (if you couldn’t already tell, the inspiration for the name of this publication). The donut hole is essentially a coverage gap where a patient is responsible for an outsized portion of their drug costs. The amount a patient has to pay in the coverage gap has narrowed over the past few years, but the donut hole can still cause a sharp increase in out-of-pocket costs for seniors. In 2021, the gap period starts once the patient and their plan spend a combined $4,130 on covered drugs. Up until this point, the patient is only responsible for their standard copays or coinsurance. Once in the donut hole, the patient pays 25% of the total cost of the drug, regardless of formulary tier. This design usually increases the cost burden for patients on biologics and other branded medications. After the patient and plan reach $6,550 of annual spending, the patient moves into the catastrophic coverage phase and only pays for 5% of drug costs until the end of the year.

The Cost Reality

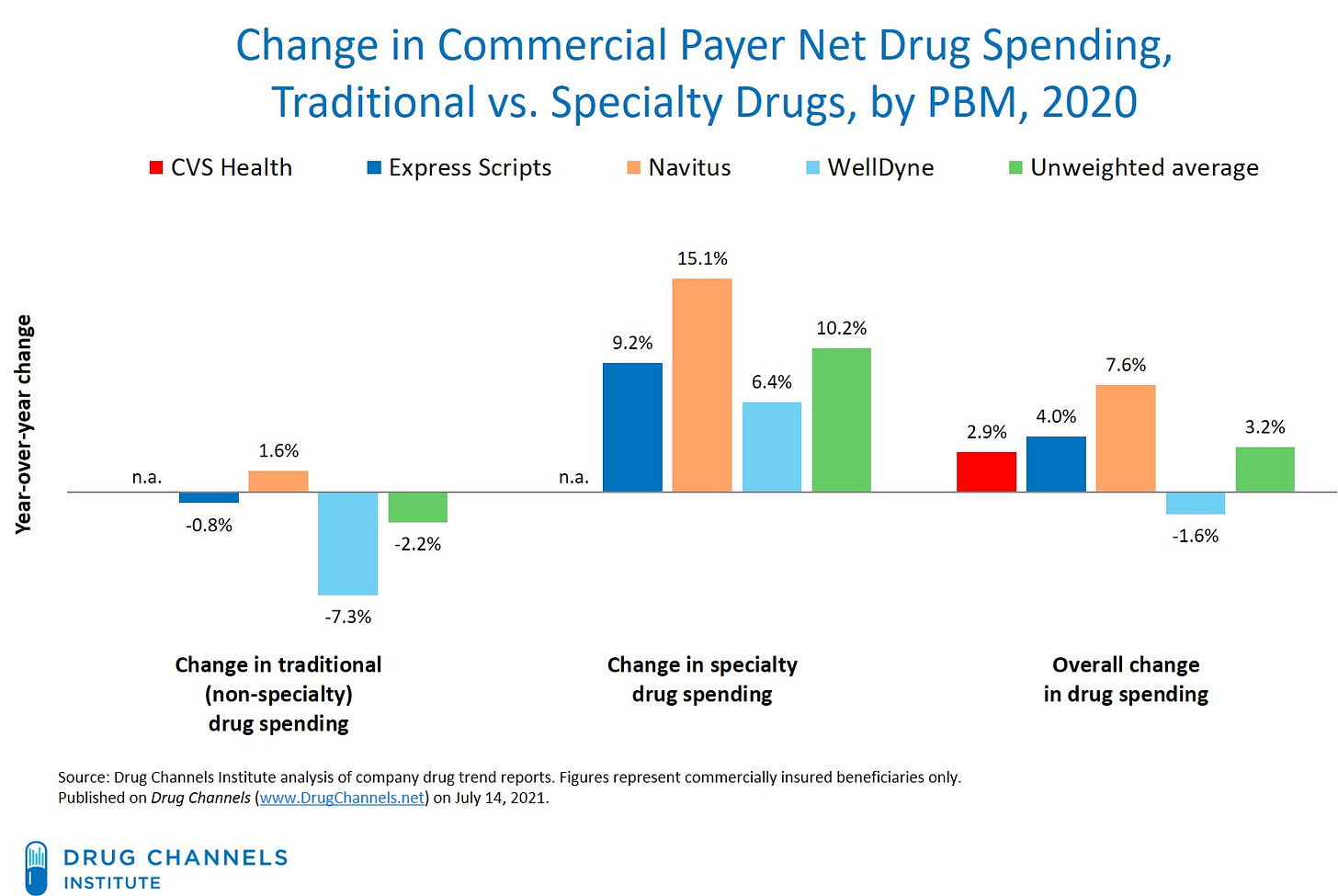

OK, but what does this all mean for drug costs? Overall, net pending grew low single-digits for most PBM-administered plans in 2020. Furthermore, most of the spending increase was due to higher utilization for specialty drugs, not higher prices (data below again thanks to Drug Channels). Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) data tell a similar story of stable drug prices with upticks in utilization.

Additionally, the U.S. leads the industrialized world in the share of prescription volume for unbranded generics (which have the lowest costs for patients and health plans). It’s one of the few things the American healthcare system does really well. Add in the innovative approaches from Amazon Pharmacy, Ro, Walmart and others and patients can now get certain generic medications for as little as $1 per month.

But drug costs nevertheless remain a significant barrier for many Americans. In a recent survey, 44% of Americans reported that they skipped filling a script in the past year due to costs. Taking a step back to a broader population, Medicare data analysis from KFF highlights the wide spread of out of pocket costs. For many Part D enrollees, the system largely works. They are on generic medications and face minimal out-of-pocket costs. But for others, those who require expensive biologics and other drugs to treat cancer, autoimmune conditions, neuromuscular disorders, and other complex conditions, drug costs present a huge financial challenge.

In effect, our system places an enormous cost burden on those with complex diseases (which are nearly always out of their control) while those who have common conditions may pay very little for drugs. This is what we mean by reverse insurance.

Possible Solutions

So what can be done to fix the out-of-pocket drug cost problem? Below are a few ideas that could help remedy the current situation.

Plan design reform

Either through regulation or private market innovation, we could support new plan design models that significantly reduce cost sharing for Tier 2, 3, and 4 drugs or greatly lower annual out-of-pocket maximums in exchange for slightly higher premiums on the whole enrolled population. As the KFF Part D example above shows, the percentage of individuals who fall into this high cost cohort is typically fairly small (only ~3% in their data). A minor premium increase on everyone would go a long way towards helping this small population.

Tying coinsurance to net prices

As mentioned above, coinsurance rates are tied to a drug’s list price the majority of the time, not the list price the PBM or plan has negotiated with a biopharma company. Instituting reforms that formally tie coinsurance amounts to net prices would provide some immediate relief for those on expensive medications. This is also something that has received bipartisan support in recent years, so hopefully this reform could actually be instituted in today’s political climate.

Discounts for adherence or ePRO

Another solution would be to leverage behavioral economics to kill two birds with one stone. More plans could institute solutions like Sempre Health, which works with health plans to reward patients who remain adherent with copay discounts. Offerings like this could be particularly impactful for medications for chronic conditions like diabetes, hypertension, and asthma.

Another similar idea would be to offer discounts to patients who complete patient reported outcomes surveys. This would be particularly applicable to those on newer therapies or those taking the drug off label. The data from these surveys around side effects, safety, efficacy, and other factors could be extremely valuable to health plans and biopharma companies and justify a significantly reduced copay or coinsurance amount.

Broaden access to copay assistance programs

Expensive copays and coinsurance have been around for a while, and the biopharma industry pioneered a patient-friendly, albeit incredibly self-serving, solution. Copay assistance programs offer substantial out-of-pocket cost relief for patients on expensive therapies. They are typically run through “independent” charities sponsored by biopharma companies (a very murky legal issue). They can be helpful for those on commercial insurance who qualify, but most programs are not available to those on government-sponsored plans, like Medicare Part D, due to anti-kickback regulations. To help more people, CMS could look at relaxing these rules or broadening the Medicare Coverage Gap Discount Program.

There is some hope. CMS is testing a new savings model that would cap monthly out-of-pocket costs for insulin for Part D enrollees at $35. Participating enrollees are expected to save an average of $446 per year with this program, which will presumably help then remain adherent.

Conclusion

America’s drug pricing problem is multi-faceted and complicated. Yes, biopharma companies could stop raising list prices, abandon anti-competitive patent thicket strategies, or be subjected to federal price controls. But we should also focus on drug plan design and institute reforms that will help people afford the medication they need.

Other news you may like:

CMMI wants every Medicare beneficiary in an accountable care plan by 2030

UnitedHealthcare to launch virtual-first primary care plan by end of year

Amid a health tech consolidation wave, Everly Health acquires fertility startup Natalist

23andMe jumps into telehealth, prescription drug delivery with $400M buyout of Lemonaid Health

Follow us on Twitter to never miss an update!

Have any comments, questions, or suggestions?

If you’re not already a subscriber, sign up now so you don’t miss the next update!