Deep Dive 4: Slashing our way through patent thickets

How pharma companies leverage a complex legal strategy to maintain monopolies

We hope you’ve enjoyed our deep dives thus far. To make them easier to find in the future for longtime and new subscribers alike, we’ve added a table of contents to our homepage that contains the links to the previous deep dives. With that housekeeping out of the way, let’s get to the fun part!

In our drug plan design deep dive, we highlighted the reverse insurance reality of today’s prescription drug coverage that harms patients who need expensive therapies. While the blame for that falls almost entirely on pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), health plans, and self-insured employers, we noted that biotech and pharmaceutical companies (referred to as biopharma moving forward for simplicity) deserve their fair share of criticism in the drug pricing debate. One of the more insidious tactics the biopharma industry employs, and the subject of today’s deep dive, is the patent thicket.

What is a patent thicket?

A patent thicket, as Wikipedia summarizes so well, is “a dense web of overlapping intellectual property rights that a company must hack its way through in order to actually commercialize new technology.” Basically, it is an intellectual property-based barrier to entry. Let’s look at a non-healthcare example first - the smartphone. This article from the World Intellectual Property Organization highlights the issue.

You pick up your smart phone with its curved sides (US Patent No. D618,677), swipe your finger across the screen to unlock it (US Patent No. 8,046,721), check email that was “pushed” to the phone without a request to the server (US Patent No. 6,272,333), and type a text message using only a few touches as the phone automatically completes each word you start to spell (US Patent No. 8,074,172). Guess what? You may be accused of violating these patents or dozens more by using inventions without a valid license.

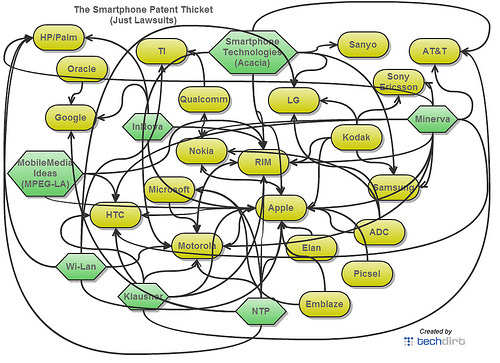

There is a war going on – with patent infringement accusations being fired regularly at Apple, Samsung, Google, Research in Motion, Microsoft, Nokia, Motorola, HTC and others. Where there are accusations of infringement, there are lawsuits.

Here’s a graphic from Techdirt from 2012 visualizing the complexity. Each arrow represents a lawsuit for patent infringement.

So let’s say you are a new entrant to the smartphone industry in 2021. You either need to invent novel methods for every little bit of smartphone functionality or negotiate a licensing agreement for each component from the respective patent holder. Either task is at worst impossible and at best incredibly arduous and time consuming. That is a patent thicket.

How the biopharma industry uses patent thickets

In the biopharma industry, patent thickets have similar anticompetitive implications. The difference, though, is that the relevant patents around a therapy are typically held by a single entity, the drug’s manufacturer. The manufacturer can then leverage the patent portfolio to keep would-be competitors out of the market.

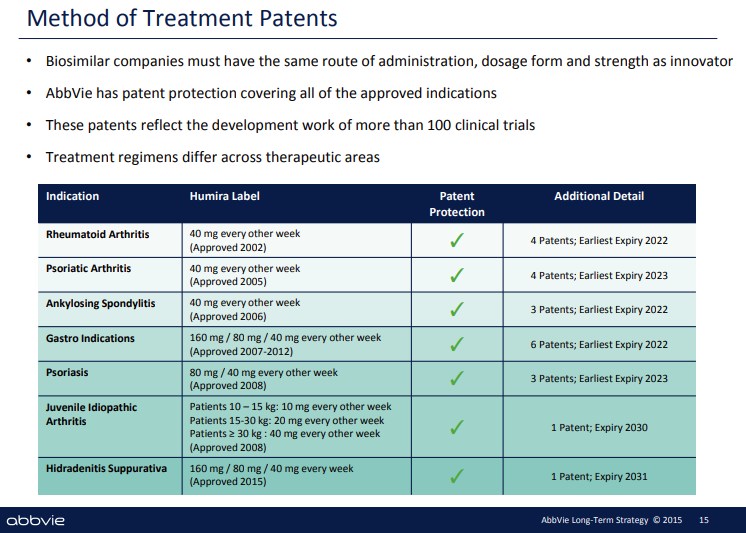

Let’s look at the best example of abusive biopharma patent thickets - AbbVie’s Humira (adalimumab for the clinicians reading this). [Quick note - a big shout out to Olivia Webb’s piece on AbbVie’s patent strategy on her blog, Acute Condition. We encourage you all to read her work for additional detail on AbbVie’s shenanigans.] As we mentioned in our first Deep Dive, Humira, which is used to treat a range of autoimmune conditions, is the most commercially successful drug in human history. The therapy brought in nearly $20B of sales in 2020, $16B of which was in the U.S. That’s an enormous number, but even crazier is that Humira’s composition of matter patent, the patent that covers the actual composition of the drug, expired in 2016 following the standard 20 year protection period. Theoretically, the company should have faced immediate and robust competition from biosimilars, what the generic versions of biologic medications are called, as soon as the composition of matter patent expired. But that didn’t happen. Why? Because Abbvie created a dense patent thicket around Humira that made it nearly impossible for other biopharma companies to enter the market. Below are slides from an AbbVie strategy deck that lays out the approach. The company obtained at least 75 other patents that cover everything from manufacturing techniques to drug administration mechanisms and more. Even more egregious is that they significantly ramped up patent applications as the composition of matter patent expiration approached. Abbvie obtained 21 patents in 2016 and 32 in 2015.

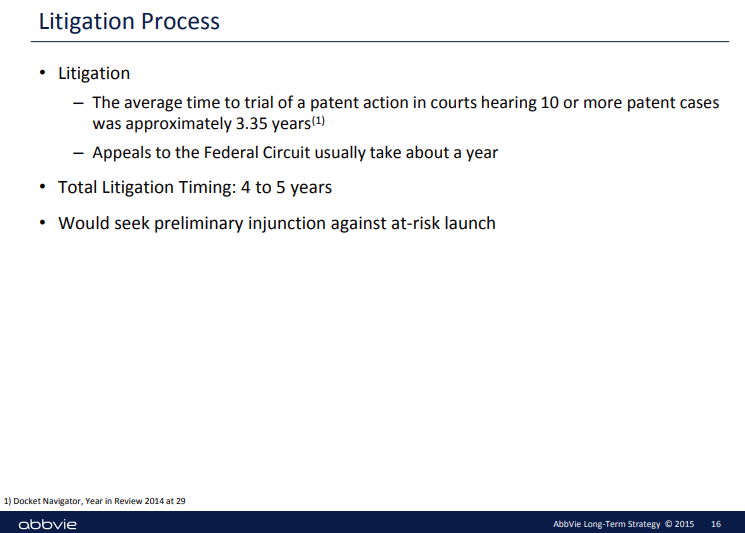

So how has this patent thicket worked in practice? It has forced would-be entrants, i.e. biosimilars, to either litigate the legitimacy of some of the patents, which can take years, or strike licensing deals with AbbVie to use a patented process in exchange for a royalty or agreed-upon market entry date. Either way, AbbVie wins. The company keeps competitors out of the market or secures some sort of financial compensation for their market entry. Below is a slide from the same strategy deck highlighting the lengthy patent litigation process for investors as well as a list of license agreements AbbVie has entered with other biopharma companies (per Olivia Webb’s piece).

While Humira is the best example of the patent thicket in biopharma, they are not alone. Below is a graphic from 2017 that shows the patent thicket strategies for top selling drugs (source). This is a widespread industry practice.

How patent thickets harm patients

Patent thickets delay biosimilar competition, and that delay carries negative financial consequences for patients and the general public. Furthermore, the practice of applying for a flurry of patents in a drug’s final few years of composition of matter exclusivity creates significant uncertainty for would-be competitors and a de facto barrier independent of the patents’ actual validity.

Higher total drug spend

The first consequence is higher drug spend for the entire U.S. system, which leads to more expensive prescription drug coverage for everyone. To see how large of an impact Humira biosimilars could have, we only need to look to the U.K.’s experience. Humira lost European patent protection in October 2018, and in a little less than a year the U.K.’s National Health Service (NHS) saved $134M by using biosimilars. While this may not seem like a lot, the NHS reported spending $487M on Humira each year while the drug was still under patent, so the $134M represents a savings of 28%. In 2020, IQVIA estimated that broader availability and use of biosimilars could reduce U.S. drug costs by over $100B from 2020-2024, savings that could help lower health plan premiums or reduce cost sharing for all Americans.

Higher expenses for individuals on therapy

As we discussed in our drug plan design Deep Dive, most individuals on biologics pay expensive coinsurance rates every time they fill a prescription. If we aren’t going to redesign our drug plans to reduce the financial burdens on those of us who need these therapies, the next best way to lower costs for individuals is to promote biosimilar competition. Savings for individuals will vary based on their specific therapy and the number of biosimilars available, but some biosimilars on the market today are priced as much as 50% below the reference brand.

Increased uncertainty for biopharma companies looking to launch biosimilars

Just the threat of patent thickets can create uncertainty and a de facto barrier to entry. Biosimilar development can take 5-9 tears and cost over $100M. If you were a biopharma executive trying to decide whether or not to develop a biosimilar for a highly successful reference product (e.g. Humira) with a target lunch date of 10 years in the future, the threat of the development of a patent thicket would undoubtedly be a core factor in your decision around pursuing the project. After all, it would be a shame to invest so much time and money only to then have a lengthy and costly legal battle over newly issued patents impact your ability to launch the product.

It is true that biosimilars can launch “at risk,” meaning that patent disputes can be ongoing at the time of launch. From 2014 to 2020, 9 of 28 approved biosimilars, 32%, were launched at risk. But this is by definition not the norm and appears to only occur when the patent thicket is weak and not expected to hold up in court. As the Humira example demonstrates, the legal uncertainty encourages biosimilar developers to either settle with the original manufacturer and delay market entry or avoid development and commercialization all together.

Potential solutions

Limiting the impact of patent thickets seems like a solvable problem. Unfortunately, though, we suspect federal action of some kind would be required to curb patent thicket abuses. With a powerful pharma industry lobby and a polarized political climate, we are skeptical that any meaningful reforms will actually be enacted. Nevertheless, let’s talk solutions.

Resolution via the courts

There are several active lawsuits concerning Humira’s patent thickets, including the City of Baltimore vs. AbbVie (court filing here) and UFCW Local 1500 Welfare Fund, the largest grocery-worker union in New York State, vs. AbbVie (court filing here). Patent and antitrust attorneys would be much better resources than us to discuss the implications of the cases, but basically rulings against AbbVie could make it easier for biosimilar manufacturers to win future litigation and bring their products to market faster. Court cases are time consuming, though, and any ruling could be subject to future appeals.

Congressional action

The Congressional Research Service published the Drug Pricing and Pharmaceutical Patenting Practices report in 2020 that highlighted several proposals for addressing biopharma patent system abuses. They include:

Passing new legislation or amending existing antitrust legislation to more explicitly address anticompetitive patent thickets

Strengthening the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) to give patent examiners more time and resources to investigate if a patent application is truly inventive.

Enhancing patentability standards for later-filed or secondary patents to make it more difficult to amass a patent thicket based on minor product or manufacturing tweaks. Interestingly, India has already taken this approach and does not allow patents for “a new form of a known substance which does not result in enhancement of the known efficacy of that substance.”

Amending certain provisions of the Hatch-Waxman Act to increase biologic patent transparency, streamline the patent challenge process, and limit the availability of the thirty-month stay.

Providing an explicit date for biosimilar competition, i.e. ensuring that patents do not create a bar to biosimilar competition upon expiration of the 12-year term of exclusivity under the Biologics Price Competition and Innovation Act.

Conclusion

Patent thickets are an abusive industry practice that raise prices for everyone and make necessary medications harder to access for millions. Reforms will be difficult since most solutions require Congressional action, but we hope that common sense proposals will break through the gridlock. Afterall, what’s more American than increasing competition!

Industry news you may have missed:

Cigna study: How behavioral health treatment can lower total cost of care

Report: Most physicians worry telehealth made them miss signs of drug abuse during the pandemic

CVS unveils new health-focused retail strategy, explicit move into primary care

Study: Digital tools don’t improve physical activity for people with low socioeconomic status

AppliedVR’s EaseVRx scores FDA De Novo clearance for treating chronic lower back pain

Have a great Thanksgiving!

— Hannah and Caleb Bank, Co-founders

Want to know more about who we are? Read our “About” page!

Follow us on Twitter to never miss an update!

Have any comments, questions, or suggestions?

If you’re not already a subscriber, sign up now so you don’t miss the next issue!